Fairness: A Fragile Currency

When people believe the rules are rigged, they disengage, protest, or even revolt, eroding the very foundations of trust that hold communities, economies, and nations together.

The American Crisis of Fairness

On a cool March morning in 2008, in the heart of Stockton, California, a young couple stood outside the courthouse. Their home, once a symbol of stability and aspiration, was about to be auctioned off. Just a few years earlier, they had signed mortgage papers with excitement, believing in the American promise that if you worked hard, saved a little, and invested in a home, you would secure a foothold in the middle class. But by 2008, that promise collapsed. Their jobs had disappeared in the recession, the adjustable-rate mortgage ballooned, and they found themselves unable to keep up. As they watched strangers bid on the house where they had celebrated birthdays and first steps, they could not help but feel that the system had betrayed them.

This couple was not alone. Across America, millions of families faced similar scenes. Foreclosures swept through suburban neighborhoods, transforming once-thriving communities into hollow shells. Rows of empty homes, with brown lawns and foreclosure notices taped to the doors, became physical manifestations of a dream deferred. What made this story more corrosive than personal misfortune was the contrast.

As they lost their homes, Wall Street bankers whose reckless bets had fueled the housing bubble were being bailed out with taxpayer money. While families were packing boxes and sleeping in cars, executives at financial institutions like AIG and Merrill Lynch were receiving multimillion-dollar bonuses.

To many ordinary Americans, this was more than an economic crisis. It was a moral one. The bailout of banks, orchestrated under the rationale of preventing systemic collapse, sent a chilling message: some institutions were too big to fail, while individuals were on their own. The sense that rules worked differently depending on who you were—that the powerful received help while the vulnerable were left to fend for themselves—cut deep. It wasn’t just inequality in income or wealth. It was unfairness in the very operation of the economic and political system.

That sense of injustice permeated every level of society. Small business owners who had paid taxes diligently for years couldn’t get bridge loans. College graduates entered a frozen job market, burdened with debt. Pensioners saw their retirement funds dwindle. Meanwhile, the architects of financial disaster faced no jail time and little public accountability. Congressional hearings were filled with vague apologies but few consequences. The symbolic heart of capitalism—that rewards follow risk and responsibility—appeared broken.

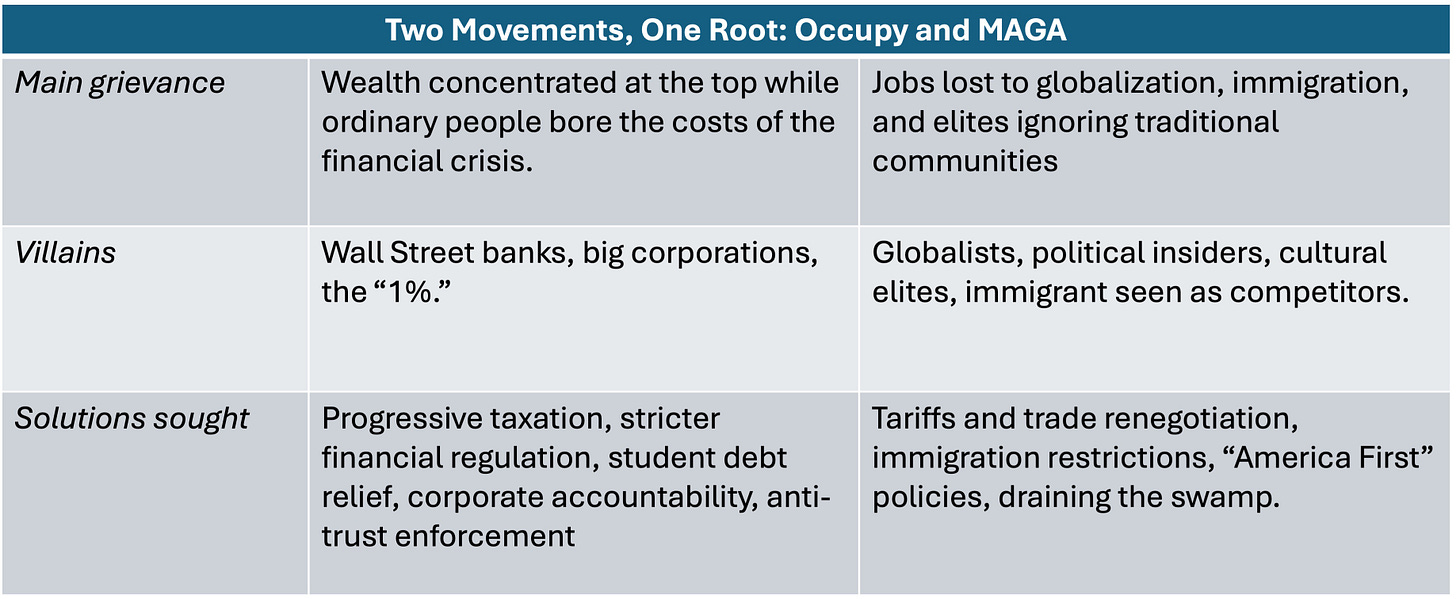

The damage wasn’t just economic. Trust in government and financial institutions plummeted. Movements like Occupy Wall Street channeled the anger of a generation that felt robbed of a future. The Tea Party emerged from a different ideological place but voiced a similar fury about elites and rigged systems. Both left and right seemed to agree on one thing: something had gone profoundly wrong.

What happened in Stockton, and in cities across the country, was not just a housing market correction. It was a crack in the foundation of the American social contract. The idea that merit and hard work would lead to stability was undermined by the spectacle of failure without consequences for the powerful. Fairness—the invisible glue that holds democracies and markets together—had frayed.

This wasn’t the first time America faced a test of fairness, nor would it be the last. And, America isn’t alone. The 2008 financial crisis revealed how deeply public confidence depends not just on outcomes, but on the perceived legitimacy of the system that produces them. When that faith erodes, the consequences are not limited to economics. They ripple into politics, culture, and the very soul of a nation.

Lessons from the Past

The story of unfairness destabilizing societies is not new, and history offers sobering lessons. In the Gilded Age of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, industrialists like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller amassed fortunes that towered over the rest of society. Their wealth symbolized not only economic power but also a growing chasm between the elites and the working masses. Factory workers endured grueling hours in hazardous conditions for meager pay, while their employers built opulent mansions and wielded influence over politics. The stark contrast wasn’t just a matter of numbers—it was a narrative of moral imbalance. The public perception that the system favored the few at the expense of the many sparked union movements, populist uprisings, and eventually led to landmark reforms: antitrust legislation, child labor laws, and progressive taxation.

Even Andrew Carnegie, one of the era’s wealthiest men, seemed troubled by the implications. In his essay “The Gospel of Wealth,” Carnegie argued that those who had accumulated great fortunes had a moral obligation to use their wealth for the public good. But this redistribution was framed as a personal duty rather than a systemic fix. It was paternalistic, resting on the good intentions of the wealthy rather than addressing structural inequities. True reform—the kind that institutionalizes fairness—came only through political pressure and agitation. Labor strikes, muckraking journalism, and the Progressive movement brought about regulatory and legal changes that aimed to restore some measure of balance.

Similar dynamics unfolded across the Atlantic in Weimar Germany, where the perception of economic unfairness proved catastrophic. The hyperinflation of 1923 did more than wipe out savings; it demolished the moral foundation of the economic system. Middle-class families who had worked hard, saved diligently, and contributed to the economy saw their life savings evaporate overnight. In contrast, those who held hard assets or had access to foreign currencies often emerged wealthier, simply by virtue of timing or luck. This inversion of reward and effort bred a toxic resentment. The social contract fractured, and with it, democratic norms.

Economic collapse opened the door to political extremism. Hitler’s rise to power cannot be separated from the grievances sown by perceived unfairness. The Nazi party exploited narratives of betrayal, injustice, and humiliation. The erosion of fairness in economic life undermined faith in democratic institutions, replacing them with authoritarian promises of order, restitution, and national revival.

These patterns have echoed through other parts of the world as well. In Latin America, Argentina’s repeated debt crises eroded public confidence in both democratic governance and market economics. Each cycle of inflation and austerity widened the perception that the system was rigged against ordinary people. Venezuela, once among the wealthiest nations in the region, saw its economy unravel under the weight of corruption, mismanagement, and politicized redistribution. As food lines grew and basic services collapsed, the sense of systemic betrayal became widespread, contributing to mass emigration and social despair.

What binds these disparate examples—Carnegie’s America, Weimar Germany, modern-day Venezuela—is the central role of perceived fairness in holding societies together. It’s not inequality alone that causes the collapse, but the sense that rules are rigged, rewards are unjust, and dignity is denied. Fairness, in this sense, functions as a kind of civic glue: invisible yet essential. When it dissolves, the structures it supports—democratic institutions, social trust, and market legitimacy—begin to crack.

Fairness as a currency

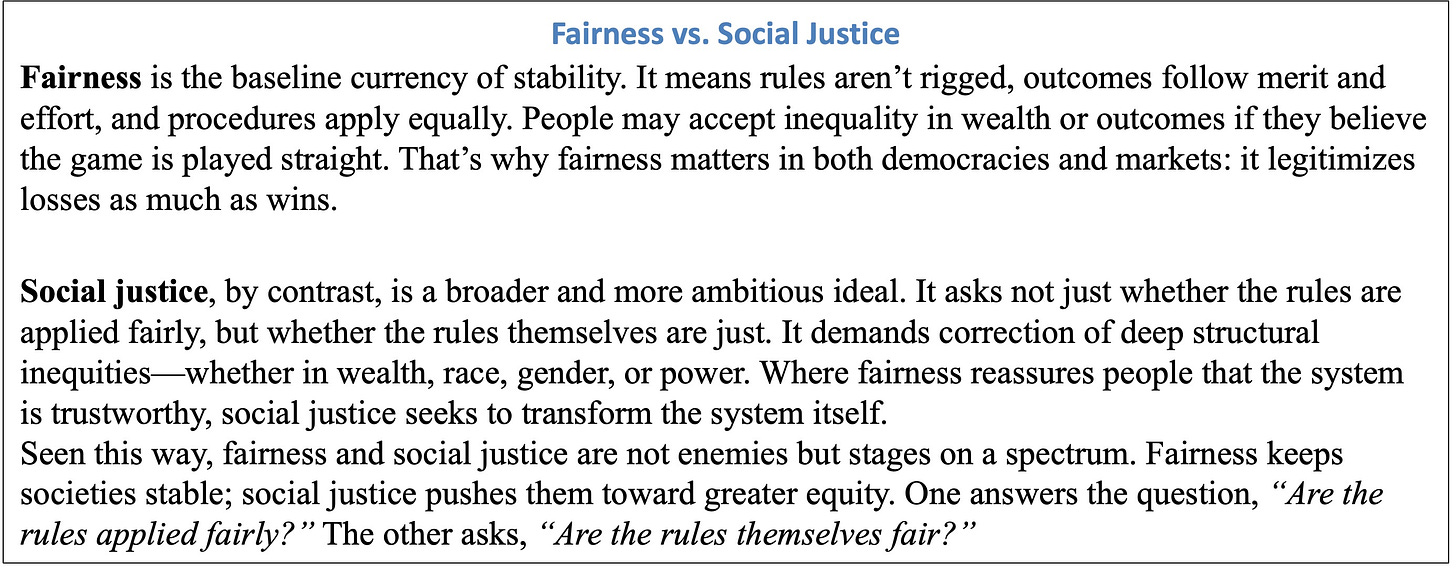

Fairness operates as a kind of hidden currency in both democracies and markets. It is the trust that fuels participation, the belief that the game is worth playing because the rules are clear and evenly applied. Economists distinguish between two dimensions of fairness: distributive fairness, which concerns how resources and rewards are allocated, and procedural fairness, which pertains to the integrity of the process by which decisions are made. Both matter deeply. One speaks to outcomes; the other to legitimacy.

Consider the findings of behavioral economics, especially the now-famous ultimatum game. In this simple experiment, one player is given a sum of money and must offer a portion of it to a second player. If the second player accepts, both keep the money as proposed. If the offer is rejected, neither gets anything. Classical economic theory suggests the second player should accept any offer above zero—something is better than nothing. But in practice, lowball offers are often rejected. People are willing to sacrifice their own gain to punish what they perceive as unfair behavior. This isn’t irrationality; it’s a profound statement about human values. Fairness matters, sometimes more than efficiency.

These laboratory insights have real-world analogs. Societies, like individuals, will turn down seemingly beneficial arrangements if they come at the cost of dignity, justice, or moral balance. For example, countries that feel they are unfairly treated in international trade agreements may impose retaliatory tariffs even if it hurts their own economies. Citizens who perceive corruption or cronyism in government may disengage from civic life or turn to populist leaders who promise to restore justice, even at great risk.

The consequences of perceived unfairness go far beyond protest votes. When citizens lose faith in procedural fairness—when they believe laws are enforced selectively, that justice is for sale, or that the powerful operate by a different set of rules—they begin to withdraw their consent to be governed. This is especially dangerous in democracies, where legitimacy rests not on coercion but on shared belief in the rule of law and equal representation. A traffic ticket handed to a wealthy donor may be seen as a nuisance; the same ticket ignored while the poor face jail time for minor infractions signals a deeper rot.

In markets, too, fairness is foundational. If competition is distorted by monopolistic practices, insider trading, or favoritism, then the invisible hand of the market starts to falter. Entrepreneurs are less likely to innovate if they believe incumbents can block entry through regulation or influence. Workers are less likely to invest in education or training if they suspect advancement is determined by connections rather than merit. Over time, the promise of capitalism—that talent and effort lead to success—is undermined.

This erosion of fairness need not be overt. Sometimes, it’s the quiet accumulation of advantages—elite college admissions skewed by legacy status, tax loopholes available only to the wealthy, zoning rules that keep housing scarce and unaffordable. These structural imbalances may appear technocratic, but they fuel a broader narrative: that the system is rigged. And when that narrative takes hold, it is incredibly difficult to dislodge.

Ultimately, fairness functions as a civic currency. It is not issued by central banks or codified in spreadsheets, but it is traded daily in the transactions of trust: between citizen and state, buyer and seller, employer and employee. When this currency is abundant, societies flourish. When it is scarce, they fragment. That is why fairness is not just a moral nicety. It is a strategic necessity for any society that aspires to be free, prosperous, and enduring.

A Cross-Ideological Convergence

It would be a mistake to think only left-leaning thinkers stress fairness. Karl Marx certainly did, seeing inequality as a driver of systemic collapse. In his theory of historical materialism, Marx argued that capitalism’s internal contradictions would eventually lead to its downfall, driven by the accumulation of capital in the hands of a few and the immiseration of the working class. He didn’t simply highlight inequality as an unfortunate side effect of capitalism; he saw it as a structural flaw that undermined the legitimacy and sustainability of the system itself. For Marx, when the working masses perceive that the fruits of their labor are unjustly appropriated, the seeds of revolution are sown. This wasn’t just a theoretical prediction: it was grounded in the observed suffering and unrest of industrial-era Europe.

But Marx was not alone. Alexis de Tocqueville, a 19th-century French aristocrat and political thinker with more conservative instincts, also saw fairness as a prerequisite for democratic health. In “Democracy in America,” Tocqueville warned that even in a nominally equal society, perceived injustice could unravel democratic institutions. He observed that citizens were more sensitive to relative status than absolute conditions. If the gap between the elite and the average citizen became too wide—not only economically, but in terms of voice, dignity, and treatment by institutions—resentment could build and democratic cohesion could falter. His insight was prescient: it is not just poverty, but the sense of being treated unfairly by the system, that fractures democratic legitimacy.

Even Adam Smith, often portrayed as the intellectual godfather of free-market capitalism, placed moral sentiments at the heart of his economic philosophy. In his earlier work, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” Smith explored how empathy, justice, and social norms underpin market behavior. He believed that capitalism could only function properly when guided by a shared sense of right and wrong. In Smith’s view, a functioning market required not just competition and self-interest, but a moral framework in which actors restrained their worst impulses. When CEOs enrich themselves at the expense of workers, or when monopolists rig the rules, they violate not just economic efficiency, but the moral norms that sustain market legitimacy. Smith’s markets were embedded in communities and social expectations—far from the caricature of markets as moral vacuums.

Friedrich Hayek, a champion of classical liberalism, fiercely opposed central planning and state-led redistribution. But even he placed great value on fairness—though he defined it procedurally rather than in terms of outcomes. Hayek warned against arbitrary government interference, arguing that the rule of law was essential to liberty. For Hayek, fairness meant that rules applied equally to all, and that outcomes emerged from voluntary exchange under general, stable rules. He saw danger in the discretionary use of power, where governments favor some and penalize others without a transparent and consistent framework. In this sense, Hayek’s concern with fairness was rooted in predictability and institutional trust. He feared that when rules are bent to favor elites or cronies, not only is freedom lost, but belief in the system erodes.

Milton Friedman, another pillar of free-market economics, held similar views. Though skeptical of government redistribution, Friedman emphasized equality of opportunity. In his seminal book “Capitalism and Freedom,” he argued that while markets could not guarantee equal outcomes, they must provide a fair starting point. Public education, for instance, was not only justified but necessary to ensure that every individual had a shot at success. Without this basic fairness, Friedman warned, capitalism risked losing its moral authority and democratic support. His notion of fairness didn’t rest on equal wealth, but on the freedom to pursue one’s goals on a level playing field.

More recently, economists like Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales have carried this thread into the 21st century. In “Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists,” they argue that markets can only remain free and vibrant if competition is preserved. When entrenched interests capture regulators, write rules in their favor, or erect barriers to entry, they choke off the dynamism and fairness that justify capitalism in the first place. Rajan, a former IMF Chief Economist and central banker, is no firebrand leftist. Yet he and Zingales caution that inequality in market access—whether in capital, education, or opportunity—undermines the social compact. Their critique echoes Smith and Friedman: capitalism thrives not on privilege, but on openness.

Thus, from Marx to Hayek, from Tocqueville to Friedman, and from Smith to Rajan, there is surprising consensus: fairness is essential to stability. Though they define it differently—as equity of outcome, process, opportunity, or moral sentiment—these thinkers converge on one point: when people lose faith that the system is fair, the system itself begins to unravel. Whether through revolution, voter backlash, or creeping authoritarianism, the erosion of fairness is the true existential threat to both democracy and capitalism. It is not merely a question of compassion or justice. It is about survival.

Fairness Across Regimes

In democracies, fairness is not just an aspiration—it is the very foundation of legitimacy. The reason citizens accept the messy outcomes of elections or the unequal distribution of wealth in markets is not because they like losing or earning less, but because they believe the process itself is fair. When voters are confident that ballots are counted honestly and that every citizen has an equal voice, even the losing side tends to accept results without resorting to violence. This is why the peaceful transfer of power in the United States has been celebrated for centuries as a hallmark of democratic stability. When that belief erodes—whether through genuine flaws in the system or through the deliberate creation of a false narrative that the system is corrupt—the social contract that underpins democracy begins to fray. In such a climate, losing is no longer seen as the result of fair competition but as evidence of manipulation or conspiracy, making violence, unrest, or outright rejection of the system seem justified to those who feel disenfranchised. The system works not because everyone wins, but because everyone believes they had a fair shot at winning.

The same is true in markets. Most workers accept that CEOs make more money, investors take home bigger returns, or entrepreneurs become billionaires, so long as the rules of competition are applied evenly. If a factory worker believes she can bargain collectively, move up in her career, or start her own business, she accepts disparities in outcomes. But when the perception takes hold that outcomes are rigged—that promotions go to insiders, that markets are cornered by monopolies, or that elections are manipulated—the entire framework begins to wobble. Legitimacy is not abstract: it lives or dies in these perceptions of fairness.

Autocracies, by contrast, rely less on procedural fairness and more on what political scientists call performance legitimacy. Citizens are asked not to judge whether rules are fair, but whether rulers deliver prosperity and stability. China provides the most striking example today. For decades, its leadership has justified centralized power with an implicit bargain: citizens surrender certain freedoms in exchange for rapid economic growth. But as inequality deepens and social mobility narrows, Beijing itself has recognized the danger. Its campaign for “common prosperity,” launched by Xi Jinping in 2021, is not simply an economic policy. It is a political signal that the government understands fairness matters—even in a one-party system. By curbing the excesses of tech billionaires and promising to redistribute opportunities, the leadership is attempting to shore up legitimacy in the absence of electoral accountability.

History shows that when fairness is ignored, even strong regimes can unravel. The Arab Spring is a case in point. In 2010, a young Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after being humiliated by local officials who demanded bribes and confiscated his goods. His act was not just a protest against personal misfortune; it symbolized the crushing unfairness felt by millions of young people across North Africa and the Middle East. They faced high unemployment despite being educated, endured corruption that rewarded connections over merit, and lived under regimes that hoarded wealth for ruling elites. What began as outrage in a provincial town quickly cascaded into a regional revolution, toppling governments in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, and shaking monarchies in Bahrain and Jordan. At its heart, the Arab Spring was less about ideology than about fairness: the sense that ordinary people were excluded from the prosperity and dignity promised by their societies.

The lesson is clear across systems. In democracies, fairness operates as the oxygen of legitimacy. When it is absent, people doubt institutions and withdraw consent. In autocracies, fairness may be less about procedure and more about outcomes, but its absence is equally destabilizing. Neither ballots nor batons can hold societies together indefinitely if citizens feel the deck is stacked against them. Fairness, then, is not a luxury or moral accessory. It is a political necessity—the hidden currency that determines whether regimes, democratic or authoritarian, endure or collapse.

Immigration, Globalization, and Perceptions of Unfairness

Immigration and globalization are often framed in economic terms, but their most powerful effects are social and cultural. Populist movements worldwide have tapped into the sense that communities are being transformed by forces beyond their control, and that elites are either indifferent to, or complicit in, these changes.

In the United States, the foreign-born population has grown from about 9% in 1990 to over 14% in 2023, the highest share in a century. For many communities, especially in regions hit hard by deindustrialization, immigration is viewed less as a labor issue and more as a challenge to cultural identity and social cohesion. This sentiment fuels movements like MAGA, where slogans such as “Make America Great Again” signal a desire to restore a sense of stability and belonging in a rapidly changing world.

In the U.K., immigration and EU membership were central to the Brexit debate. Between 2004 and 2016, net migration into the U.K. increased sharply, with hundreds of thousands arriving from EU member states. For voters in northern England and other post-industrial areas, the issue was less about economic data—which often showed neutral or positive effects—and more about control and voice.

In continental Europe, similar dynamics emerged. Germany’s decision to admit over one million asylum seekers in 2015 was hailed internationally as a humanitarian triumph. Yet in many small towns, the pace of change strained housing, schools, and public services, fueling perceptions that the burdens of integration were being borne by communities with little voice in policymaking. Residents in towns across Saxony and Bavaria often spoke less about economics and more about cultural fit and fairness, with the feeling that political elites in Berlin and Brussels had ignored their concerns. The AfD turned these sentiments into political capital, transforming cultural unease into electoral strength.

Globalization compounds these tensions by making borders more porous—through trade, capital flows, and digital connectivity. U.S. trade as a share of GDP climbed from roughly 20% in 1970 to over 60% by 2020, creating growth but also dislocation. Rural and post-industrial regions often experience this interconnectedness as something done to them rather than for them. Factories close, jobs disappear, and familiar cultural patterns fray, creating a narrative that merges economic loss and cultural displacement into a single story of unfairness.

Managing these tensions requires more than economic adjustment programs. It demands policies and narratives that acknowledge cultural as well as economic concerns—recognizing that fairness in a globalized world is about belonging and voice as much as it is about wages or GDP growth.

The Social and Cultural Dimensions of Unfairness

While economic dislocation often anchors the narrative of unfairness, many of today’s populist movements are animated just as strongly—sometimes even more so—by social and cultural grievances. These movements argue that the "rules of society" have been rewritten without their consent and that their values, identities, and voices have been marginalized by elites who control media, universities, and cultural institutions.

In the United States, this cultural unfairness narrative fuels resentment over what many see as the dominance of coastal, progressive values in public discourse. Policies around gender identity, policing, and education are often portrayed by populists as evidence that cultural elites impose their worldview on communities that feel unheard or disrespected. This grievance helped power the Tea Party a decade ago and now energizes the MAGA movement. For many, the outrage is less about jobs and wages and more about dignity and recognition—the sense that their identity and beliefs no longer command respect.

In many rural towns, economic shifts hollowed out local industries, but cultural shifts hit even harder. National media narratives often caricature these communities as backwards or out of step, deepening feelings of alienation. As one resident in Ohio put it, “It’s not that we don’t want change; it’s that change is happening to us, not with us.” This sentiment, repeated across countless communities, helps explain why cultural issues resonate so powerfully in populist politics.

Across Europe, similar dynamics play out. In France, the National Rally frames immigration and EU integration as existential threats to French identity and sovereignty. What began as a protest over fuel taxes in 2018 quickly evolved into a broader rebellion against what protesters saw as Parisian elites ignoring the struggles of “ordinary” France. The yellow vest became a symbol of cultural invisibility—of rural and working-class communities feeling excluded from decision-making. Here, economic grievances merged with cultural ones: a fight not just for fair taxation but for recognition and dignity.

In Germany, the AfD taps into fears that rapid demographic and cultural change erodes traditional values, while in the Netherlands and Scandinavia, populist movements question multiculturalism, arguing that the push for inclusivity has created a society that unfairly prioritizes newcomers over citizens.

In eastern Germany, where economic recovery has lagged since reunification, AfD rallies often highlight cultural grievances: declining church attendance, changing school curricula, and the sense that traditional values are dismissed by urban elites. Immigration amplifies these anxieties, creating a potent mix of economic and cultural insecurity that drives support for the far-right.

This sense of cultural dispossession often fuses with political distrust. Many populists argue that mainstream parties, global institutions, and media outlets are aligned against “ordinary people,” silencing dissenting voices and ignoring legitimate concerns. In this context, fairness is no longer only about economic opportunity but also about representation, identity, and respect.

These cultural fairness narratives can be more polarizing than economic ones because they are less amenable to compromise. Trade policies can be renegotiated and safety nets expanded, but identity-based grievances challenge the very fabric of pluralistic societies. Managing this dimension of unfairness—by creating spaces where diverse voices feel heard and by ensuring that cultural shifts are accompanied by dialogue and inclusion—may be among the most difficult but most urgent tasks for democracies in the years ahead.

Survival Through Fairness

The Stockton couple’s story is not unique; it is emblematic of a recurring pattern across time and place. In moments of crisis, whether in 2008 America, 1923 Germany, or present-day China, the common denominator is not simply inequality—it is the collapse of fairness. Inequality on its own can be tolerated, even celebrated, when it is linked to effort, innovation, or risk-taking. Americans have long admired the entrepreneur who builds a fortune, just as Germans once admired the industrious middle class that powered their economy. But when inequality translates into unfairness—when outcomes seem disconnected from merit or when the rules look rigged—the social fabric frays. People can accept losing; what they cannot accept is losing in a game they believe has been fixed from the start.

This is why fairness is the fragile currency of stability. Democracy depends on it, because elections are nothing more than a collective agreement to abide by rules and accept outcomes. If citizens believe ballots are manipulated or voices suppressed, the entire edifice crumbles. Capitalism depends on it, because markets function only when participants trust that competition is genuine and rules apply equally. When consumers believe corporations exploit them, when workers believe advancement is blocked, when investors suspect insider favoritism, the invisible hand loses its legitimacy. Fairness is not simply a moral aspiration—it is a practical requirement for systems to endure.

The warning signs are everywhere. In democracies, populist movements gain ground by insisting the system is corrupt or unfair. In autocracies, governments scramble to redistribute or control narratives when prosperity fails to mask inequality. Both responses reflect the same truth: without fairness, political and economic systems lose their legitimacy, and with it, their stability.

The lesson for our own moment is stark. The survival of democracy and capitalism does not hinge on efficiency metrics or quarterly GDP growth alone. It hinges on whether people feel they are treated with fairness—whether rules are consistent, opportunities are real, and dignity is preserved. When fairness is present, societies can endure hardship, inequality, even loss. When it is absent, no amount of wealth or force can buy stability for long.

Fairness, then, is not a luxury add-on to democracy and capitalism. It is their lifeblood. Lose it, and the structures that once seemed permanent can collapse with astonishing speed. Preserve it, and even turbulent societies can renew themselves. The challenge of our age is to recognize fairness not as an afterthought, but as the central currency that keeps our systems alive.

If the lesson of history is that fairness is the currency of stability, then the challenge of our time is to replenish it. This requires more than technical fixes or policy tweaks; it requires a cultural and political recommitment to the principle that rules must apply equally and opportunities must be genuinely open. That means confronting monopolies that choke competition—whether it’s breaking up Big Tech giants that control entire digital ecosystems or reining in financial institutions that still seem insulated from consequences. It means repairing electoral systems so that every vote counts equally, regardless of ZIP code or income level. It means ensuring that hard work and innovation—not insider access—determine who succeeds, whether in Silicon Valley, Wall Street, or Main Street. These are not partisan goals. They are the preconditions for legitimacy, shared by democrats and republicans, markets and states, left and right.

The call to action is simple but profound: rebuild fairness before trust collapses beyond repair. Societies that have done so in the past—through progressive reforms in the early 20th century, through civil rights legislation in the 1960s, through moments of renewed transparency and accountability—demonstrate that renewal is possible. Today, renewal might mean protecting voting rights from partisan manipulation, tackling campaign finance systems that amplify the wealthy few, or demanding real accountability for corporate misconduct. It might mean recognizing that fairness at work—through living wages, portable benefits, and protections for gig workers—is as essential to stability as fairness at the ballot box. The Stockton couple, the German saver, the Tunisian street vendor—these are not distant stories. They are reminders that without fairness, no system is safe. With it, even fragile institutions can endure and adapt. The future depends on which lesson we choose.